Stephen Schwartz's Career

Stay updated on Stephen Schwartz news by subscribing to the free newsletter/e-zine: The Schwartz Scene.

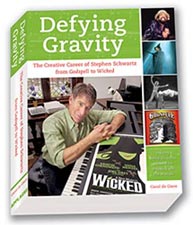

The best source for Stephen Schwartz's career is the biography Defying Gravity: the Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to Wicked. To write this book, the author drew from eighty hours of interviews with Schwartz, as well as from over 100 interviews with his colleagues, friends, and family members. Defying Gravity includes many never-before-told stories and over 200 photographs and illustrations. 544 pages. For more information or to order the book online visit DefyingGravityTheBook.com

The best source for Stephen Schwartz's career is the biography Defying Gravity: the Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to Wicked. To write this book, the author drew from eighty hours of interviews with Schwartz, as well as from over 100 interviews with his colleagues, friends, and family members. Defying Gravity includes many never-before-told stories and over 200 photographs and illustrations. 544 pages. For more information or to order the book online visit DefyingGravityTheBook.com

The following article about Stephen Schwartz's career was first published in Cabaret Scenes Magazine October and November, 2002. The article is based on interviews, and is angled towards the interest of the readers of Cabaret Scenes Magazine. Obviously some of the information is out of date but the overall content may be of interest. Readers should bear in mind that this article was written before WICKED went into rehearsals.

The following article about Stephen Schwartz's career was first published in Cabaret Scenes Magazine October and November, 2002. The article is based on interviews, and is angled towards the interest of the readers of Cabaret Scenes Magazine. Obviously some of the information is out of date but the overall content may be of interest. Readers should bear in mind that this article was written before WICKED went into rehearsals.

It is reprinted here with permission. Copyighted. [Please do not reprint without permission]

Stephen Schwartz: The Spark of Creation

by Peter Leavy

The career of Stephen Schwartz took off almost from the moment the composer/ lyricist was graduated in 1968 from Carnegie Mellon University. In 1969, he wrote the title song for the Broadway comedy Butterflies Are Free, which then was turned into a Columbia film. It might even be fair to say his star was in its ascendancy even before he was graduated, since Pippin, a musical he wrote for the college theatrical society, would hit Broadway big time just a few years later, directed by Bob Fosse and running for nearly 2000 performances. Of course, by the time the college bred Pippin got to Broadway, Godspell, with Stephen's music and lyrics, was playing Off Broadway at the Promenade Theater and was well on its way to its own 2,147 performance achievement. A song from the show, Day By Day, was in the top ten, and the cast album was in the top forty. All of this for a young talent not yet twenty five years old.

One thing is certain. By some miracle, Stephen's dazzling accomplishments have not gone to his head. with the current string of his musicals being performed literally all over the world today, he remains unassuming, approachable, and the same contemplative writer who has, since the beginning, strived ceaselessly to improve his work. And with that, he still finds time to reach out to other writers and performers to aid them where he can.

At the August Songwriters Showcase in New York, jointly produced by MAC and ASCAP with the objective of bringing together contemporary writers and cabaret performers seeking new songs for their shows, Stephen was the featured guest. The debt cabaret performers owe musical theater composers, and vice versa is clear. In the onstage interview with Jamie deRoy, Schwartz acknowledged songwriters' respect for the intimate art form. "Cabaret keeps songs alive," he pointed out. "Good songs from shows that have closed live on in cabaret. Some years ago, you could issue singles, but that's not likely to happen anymore. I feel abject gratitude to cabaret," the three time Academy Award winner and two-time Grammy winner said, "for keeping them alive."

Schwartz, composer and/or lyricist of more than a half dozen Broadway musicals and four films, expanded that appreciation when I spoke to him to include songs from shows that hadn't yet found their way to commercial production, as well as those single songs that need the cabaret exposure to be heard outside the realm of the composers' friends and families. As he puts it, "People who are writing for the theater are very unlikely to be having songs recorded by Puff Daddy. If you're writing a full length show, it will take a number of years to get it on, and the only other outlet for your music is cabaret."

An inveterate morning workaholic, he'll start as early as seven but quit by early afternoon leaving his nights free to go out. "I see a lot of cabaret. What's of great value to me is hearing someone else interpret my songs. I learn a lot about each piece of material. Sometimes I get ideas for ways to make the songs work better and I sort of steal the ideas. Sometimes I hear them not working, and I think, 'Oh, I see, if you do it this way you sort of lose the impact of the song.'" Stephen himself started performing three or four years ago, appearing by preference in small cities. "Basically, I'm performing in what you would call cabaret venues. In the places I go, usually the rooms or auditoriums seat no more than a couple of hundred."

An inveterate morning workaholic, he'll start as early as seven but quit by early afternoon leaving his nights free to go out. "I see a lot of cabaret. What's of great value to me is hearing someone else interpret my songs. I learn a lot about each piece of material. Sometimes I get ideas for ways to make the songs work better and I sort of steal the ideas. Sometimes I hear them not working, and I think, 'Oh, I see, if you do it this way you sort of lose the impact of the song.'" Stephen himself started performing three or four years ago, appearing by preference in small cities. "Basically, I'm performing in what you would call cabaret venues. In the places I go, usually the rooms or auditoriums seat no more than a couple of hundred."

As witnessed at his Songwriters Showcase appearance, Stephen is an animated vocalist as he accompanies himself on the piano, enjoying a good voice and a versatile one that moves into high notes with ease and confidence. He increasingly enjoys performing now, no longer as nervous about doing a show before an audience. And the experience has proven valuable. "There are songs that sound as if they're going to work, then they don't when you hear them in context. In these cabaret performances, I've learned how important a setup for a song is to how well it functions. I've really learned how to set up the individual songs, and to some extent that what you say to introduce a song has a great deal to do with how the audience responds to it."

Stephen sees the relationship between theater and cabaret as vital. He serves as the artistic director of ASCAP workshops for aspiring writers of musical theater, held in both LA and New York several times a year. From hundreds of submissions, ASCAP's Michael Kerker and he winnow the participants down to four writers, who then in seven or eight meetings "delve into what they're trying to achieve and seek to determine where they're successful and where they still have a way to go." And, aware of the need to hear their songs performed, "Twice a year, we have a cabaret evening, where we invite songwriters and cabaret singers," acquainting each of the groups with the other for their mutual benefit.

Although the overview of Stephen's career may sound as if success was served to him on a silver platter, coming quickly as it had, it was not without enormous effort. And having to deal with the failures that also lay ahead of him. He had had an early run of discouraging backers' auditions for Pippin. The opportunity to write a song for Butterflies Are Free was only on speculation. Of course, when it was accepted, Stephen, understandably, thought he was in clover. In the brief time he'd been in New York, he felt nothing was happening. Now, however, with Butterflies running, he received a royalty check for $25 each week of the show. For a twenty one year old, it was nirvana: "a check every week for doing nothing."

[The ever popular Godspell which has had more than 150 productions around the world in the past year alone.]

[The ever popular Godspell which has had more than 150 productions around the world in the past year alone.]

The song was indeed a notable beginning to a career, and precursor to a spectacular achievement figuratively just around the corner. Being given a chance to write new music and lyrics for the original version of Godspell, a musical playing at New York's offbeat Café La Mama, may not have seemed to portend great things. But it was a chance, and having seen the production, he "understood what the show was and what the music needed to do." He managed to write fourteen songs for the new version in just five weeks. As he said in a 1998 interview, "I was too young and too stupid to know it couldn't be done that fast."

The newly scored Godspell opened in May of 1971, and the crowds seeking tickets to its new venue at the Off-Off-Broadway Cherry Lane Theater quickly outgrew the limited seating. It moved to the uptown Promenade Theater, and after its astonishing run there, opened on Broadway for more than 500 performances at the Broadhurst Theater. Since then, the musical, which brought its young composer/lyricist multiple awards and two Grammys, has never been off the boards for long. It is an enduring favorite of local theater and amateur groups worldwide. According to author Carol de Giere, who is working on a book about Stephen and also maintains the www.musicalschwartz.com site, there have been more than a hundred and fifty productions around the world in the past year alone.

[Opening night of Mass with Leonard Bernstein leading the bows.]

[Opening night of Mass with Leonard Bernstein leading the bows.]

Other accomplishments followed Godspell in fairly rapid order. For the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., Stephen worked with Leonard Bernstein on the English lyrics for the noted composer's Mass. Then, Stephen's college musical, Pippin, the tale of the son of Charlemagne who had plotted to overthrow his father, got its Broadway production. Recalling its origins at Carnegie Mellon, Stephen said, "We were all into The Lion in Winter in those days. What family doesn't have its ups and downs? We thought it would be fun to do a musical about court intrigue, with literal and figurative backstabbing." Two years after Pippin's opening,The Magic Show was produced and would run for more than 1800 performances.

But discouragement loomed. Two years later, his then current musical theater piece, The Baker's Wife, would close out of town without reaching its hoped for run on Broadway. A similar bitter pill awaited him again some years later, when the Charles Strouse scored Rags, with lyrics by Stephen, would go dark after a paltry four performances. Of course, the failures entitled him to representation on Joe Allen restaurant's famous Wall of Flops, but to his credit, Stephen would persevere, and eventually prevail.

As he would later say in an interview with ASCAP, "with some shows, I think you can look at what didn't work and say, 'Oh, I can fix that,' and you can do it fairly easily without tearing your hair out." That was true, he notes, of the musical he adapted from Studs Terkel's book, Working, and it also was true of his more recent Children Of Eden. "I'm an inveterate tinkerer with a show until I feel I have it bullet proof. And even then sometimes, if it gets dated, like Working did, I'll go back to replace some of the material that was no longer relevant."

Reflecting on The Baker's Wife and Rags, Stephen acknowledges they "didn't really work in their initial outings." Unexpected obstacles often crop up in creating a show, but "with a little bit of tinkering, boom, it's fixed." Rags, on the other hand, which he believes is Strouse's best score, and The Baker's Wife, "were more problematic," and not so Stephen Schwartz. "Over the years, as we've tinkered with The Baker's Wife, we've gotten further away, then we've come back, and we've gotten closer. (Britain's famous director, Trevor Nunn, liked it enough a dozen years and possibly a half dozen revisions later, to stage a production on the West End in London.) "I've been very lucky," Stephen says, "in that all the shows of mine that have failed, have always gone on to rise later." He adds, "That's quite unusual," acknowledging such second time around turnabouts are more extraordinary than commonplace.

[Editor's note from 2006: The Baker's Wife was revised again for Paper Mill Playhouse in 2005. Stephen Schwartz later wrote: "I am extremely happy with the beautiful production at Paper Mill, and I'm glad you were enthusiastic about it as well. Joe Stein and I are, I think understandably, very pleased that after so many years and so much effort, the show is finally done! We both feel this is the final version, and are delighted it has been so well received."]

Stephen's obsession with getting things just so was apparent when I first arrived to interview him. In an impressively outfitted audio studio in the East Village, he was doctoring a recorded song on the 64-track equipment. Vocalist Pamela Myers had cut a CD of songs of various contemporary composers, using each songwriter as her accompanist. She had included Stephen's The Spark of Creation from his Children of Eden. While most of the other composers may have called it a day after the taping, Stephen now was meticulously going over the master to delete a tenth of a second at a point when Pamela came in a shade early. Such exacting attention is characteristic. The Baker's Wife, with its lovely numbers Chanson and Meadowlark, and Rags, from which Blame It on a Summer Night comes, both owe their successful resurrections to such attentive reworking.

It's the kind of effort he relishes. It may take years for a musical show to come to fruition, but he asserts, "I like the writing process. I like working on something, going away from it, coming back to it, and thinking how could I get this better, how could I make this right, and slowly discovering the show. It reveals itself to me over time. I enjoy it less once the show is finally written and the move to putting it into production actually happens."

Nevertheless, even then he remains in pursuit of improvement, if not perfection. Godspell, which first played with Stephen's music and lyrics more than three decades

ago, has undergone many changes over the years. His Studs Terkel based musical, Working, got its reworking twenty years after its debut, in time for the millennium. Carol de Giere notes, "I found a long list of songs written for various versions of The Baker's Wife. I showed it to him and said, 'You wrote a ton of songs for the show.' Stephen quipped, 'Millions.'" As de Giere points out, "He doesn't treat his songs as precious creations that have to be kept." Scott Schwartz, Stephen's son, now a successful musical director in his own right — he directed the surprise musical hit, Bat Boy, and co directed Broadway's Jane Eyre concurs. He claims that he never remembers a time when his dad wasn't reworking The Baker's Wife.

CONTINUES ON NEXT PAGE:

Stephen Schwartz's career part II

Note: This article was originally published in Cabaret Scenes Magazine